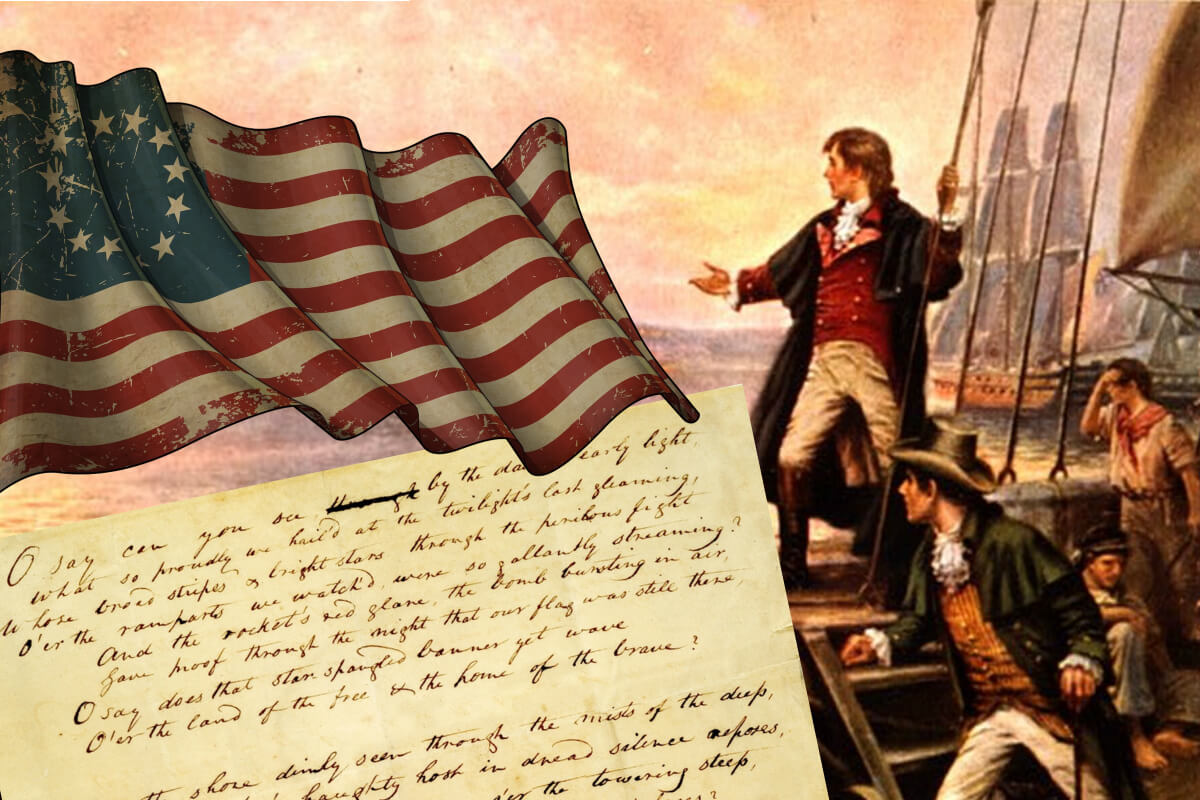

Right about now, it would do Americans good to remember the story of the attorney, Francis Scott Key, who wrote the poem, “The Defence of Fort McHenry,” that quickly became known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.” By knowing its origin, we may better handle our present-day ruckus.

The words of our national anthem describe real-life events, what was observed that fateful night in September of 1814, when the British were trying to bomb Fort McHenry off the map.

Attorney Francis Scott Key was given the task to negotiate the release of American prisoners of war, during the extended War of 1812. He boarded a British ship to strike a deal with the ship’s commander for the prisoners held in its hull.

After almost a week deliberating, he finally secured an agreement: the trade of prisoner for prisoner. Then he was told bluntly by the British officer that their deal did not matter. “Why not?” he asked.

“Because before you leave this ship we will win this war and all prisoners on both sides will be released,” the officer replied to that effect.

The United States faced a dire situation at the time. The British had just a few weeks earlier captured our capital of Washington, D.C.; President Madison and his wife had been forced to escape; and the capitol, the White House, and governmental buildings had been burned to the ground.

Currently, sixteen British battleships were sailing toward Baltimore harbor, intent on capturing the city of Baltimore.

A lone fort protected it, Fort McHenry. The British had offered the United States a simple deal: surrender. Lower the flag at Fort McHenry and it would not get bombed out of existence.

The fort’s flag, however, was no ordinary American flag. This was the star-spangled banner Mr. Key wrote about. It had been specially commissioned to be 42 feet wide and 30 feet tall. A huge flag. Secured to a huge pole that stood o’er the ramparts of the fort. It boldly stated to the British ships sailing into Baltimore harbor, “This is the land of the free.”

This awesome-sized flag so gallantly waved in proud defiance of the British. Fort McHenry, which housed about 1000 soldiers, refused to lower the flag. Indeed, it was the home of the brave.

While Mr. Key had told the prisoners in the hull of the good news about their imminent release, he also shared the bad news about the British plan to destroy Fort McHenry.

After his short-lived agreement, Francis Scott Key was detained on the ship, where he had to bear a punishment of the heart. He had to wait and watch the full force of British naval power aiming every cannon at Fort McHenry until – until her flag waved no more.

The pounding began. The prisoners heard non-stop explosions all through the night. For 25 hours, the British fired bombs at the fort.

The prisoners in the hull understood the intent of the British to impose an unfathomable, demoralizing defeat upon America. The prisoners kept asking Francis Scott, their only eyes on the battle, “Is our flag still flying?”

It was still visible at the twilight’s last gleaming Key reported to them, when he could still proudly hail it. In the dark of the night, however, only by the light of the rocket’s red glare and the bombs bursting near the flag could Mr. Key see proof that our flag was still there.

The thunder continued into the dawn’s early light. The prisoners asked him again, “Oh say, [Mr. Key] can you see [it]?”

By this time, the British had exhausted their arsenal and halted their barrage, unsuccessful in downing that statement of freedom, that cherished star-spangled banner yet waving.

The origin of this song is not an imagined one. It is an eyewitness account from the unique vantage of an attorney, huddled with prisoners of war, aboard an enemy ship that was part an armada pounding Fort McHenry to its demise.

He experienced with those prisoners ears banging, hearts anxious, and guts riveted to hope that freedom would prevail with each deafening boom. Francis Scott Key did not merely imagine up our National Anthem. He lived it.

And every time we stand at attention to hear it, we do too.